Opinion & Analysis

Which major crowns golf’s greatest champions?

This month marks the 40th anniversary of the “Massacre at Winged Foot,” the 1974 U.S. Open won by Hale Irwin at 7-over par. When senior USGA official Sandy Tatum was asked about the difficulty of the course setup, a setup at which not a single player broke par in the first round, he famously responded:

“We’re not trying to embarrass the best players in the world, we’re trying to identify them.”

With the U.S. Open at Pinehurst days away and golf’s two final majors of the year following in July and August, it’s good to recall Tatum’s memorable line and ask:

- How well does the U.S. Open or any major do at identifying golf’s greatest champions?

- Is there one that crowns the best golfers on a more consistent basis than the others?

- How would you go about proving that, or provide compelling evidence to support it, if that were the case?

To many readers, it might seem The Masters is an obvious choice for the best major at identifying golf’s greatest champions with six victories by Jack Nicklaus, four by Tiger Woods and Arnold Palmer and three each by Phil Mickelson, Gary Player and Nick Faldo. But green jackets have also been won by Gay Brewer, Charles Coody and other players whose careers do not rank with the all-time greats. What about the U.S. Open, with four victories by Bobby Jones, Ben Hogan and Nicklaus, three by Tiger and Irwin and two by Lee Trevino, Billy Casper and Ernie Els? This article outlines an approach for determining what majors have done the best at identifying golf’s greatest champions an approach that consists of a few main steps:

- Identify all major championship winners in a given period. Starting with 1960, there have been 110 individual winners of golf’s majors in 216 tournaments (54 years, four majors per year). The year 1960 is a good starting point for two reasons: first, the U.S. Open won that year by Arnold Palmer at Cherry Hills outside Denver is widely viewed as a crossroads between the modern game of Palmer and Nicklaus and the post-WWII era of Hogan and Snead. Second, in 1958, the PGA Championship shifted from match play to stroke play, so starting earlier than 1960 and still including the PGA Championship would pose an apples-to-oranges problem in comparing all four majors because we would not have comparable data for a full decade pre-1960 as we do for the 1960s, ’70s, etc.

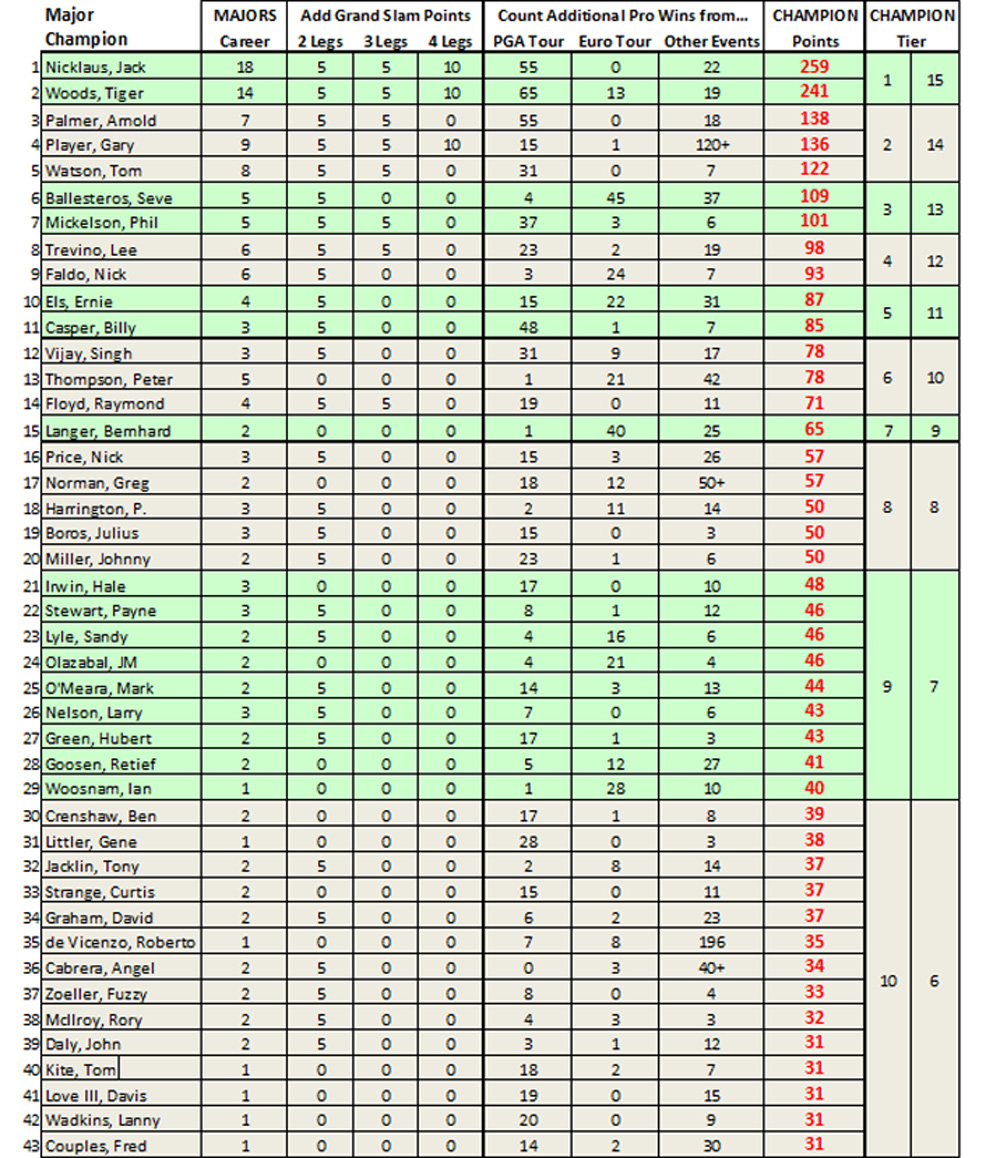

- Rank 110 major champions since 1960 based on a quantitative method that gives “champion points” for victories in the majors and for other tour wins across their career (e.g., PGA Tour, European Tour, etc). Note: If a major champion’s career accomplishments preceded 1960 — such as major victories by Arnold Palmer (1958 Masters), Gary Player (1959 Open Championship), Julius Boros (1952 U.S. Open) and a few others — these accomplishments are still counted in their “champion point” totals.

- Based on the rankings in No. 2, group all 110 major winners into smaller and more manageable “champion tiers” and then apply these tiers to each of the four majors from 1960-to-2013 based on the champion who won the major that year. By adding the “champion tier” points (1-to-15 with 15 being the highest) during a given time period for all four majors — e.g. since 1960, a decade like the 1970s, etc. — the major with the highest number of champion points can readily be identified and compared to the others.

While this approach is straightforward in concept, subjective judgments still have to be made. For example, all non-major wins on the PGA Tour are treated the same, such as Davis Love III’s two stirring victories in the Players Championship (1992 and 2003) and his one-stroke win against Tommy Gainey in the Children’s Miracle Network Classic (2008). All three are each given the same number of “champion points” in step No. 2 above, as is every win on the European Tour. What about a player’s victories on senior tours, Asian and other pro tours, his amateur record, or performance in the Ryder Cup or President’s Cup? Answers to these and other questions are found in the accompanying box on methodology and assumptions. Obviously readers will have differing views on the approach used. There clearly are many ways to quantify a major champion’s accomplishments and slight changes in methodology can lead to significantly different results. The approach proposed here is by no means definitive, but hopefully provides a reasonable starting point that can be refined and improved in time with your input.

Methodology/Assumptions

- What is counted and not counted in establishing a major champion’s record?

- How are champion points accumulated?

Major Championship Wins

- 10 champion points for each major victory.

- +5 points for winning two legs of the Grand Slam.

- +5 more points for winning three legs of the Grand Slam.

- +10 more points for winning all four majors — the Grand Slam.

So if a golfer were to win all four majors, he would be credited with 60 total champion points consisting of: 10 for each major (40), plus 20 more for winning the Grand Slam (5+5+10). If a golfer were to win only the Masters or only the U.S. Open twice, they would be credited with 20 champion points — 10 for each major, whereas a golfer winning two different legs of the Grand Slam, say the U.S. Open and PGA Championship like Rory McIlroy has done, he would be credited with 25 champion points, +5 points for winning two legs of the Grand Slam.

- PGA and European tour wins: One point awarded for each win on the PGA or European tours, regardless of the prestige of the event, quality of field, etc.

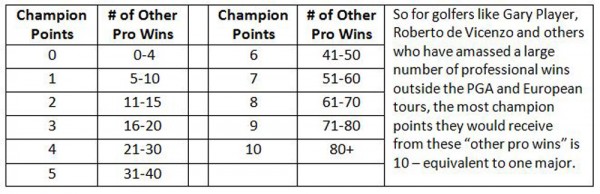

- Other professional wins: For tours in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Web.com and other professional wins, the following scale has been developed.

- A snapshot in time, year-end 2013: No attempt is made to project a current player’s career beyond his accomplishments at the end of 2013. As a player’s record grows, results can readily be updated.

Key Findings

The resulting data is a veritable gold mine of information that can yield many interesting findings about golf’s four majors and the 110 players who have won them from 1960 to 2013. Here are a few highlights: Since 1960, the past 54 years:

- The Masters is the major with the highest number of champion points. The resulting data has the Masters with 516 champion points, an average of 9.6 points per year. This is equivalent to the winner of the Masters since 1960 being a champion ranked between Nos. 12 and 15 on average in terms of career accomplishments out of all 120 major champion winners. This is truly elite status (see Top 40+ Golfers chart).

- The Open Championship (British Open) is a close No. 2 to the Masters. The Open Championship is credited with 492 champion points, just 24 points below the Masters during the 54 years. This works out to an average of 9.1 champion points per year, equivalent to the average winner of the British Open being a champion ranked No. 15 in terms of career accomplishments out of all 120 major winners since 1960 (see Top 40+ Golfers chart).

- The U.S. Open and PGA Championship are nearly tied with the fewest champion points. The U.S. Open and the PGA Championship have very similar results with 407 and 400 champion points respectively. Both are more than 100 points below the Masters. This works out to 7.5 champion points per year, which is equivalent to the average winner of these two majors being a champion ranked between Nos. 16 and 29 in terms of career accomplishments out of all 120 major champion winners since 1960 (again, see Top 40+ Golfers chart).

Winning Major by Decade, 1960s to 2000s

- The Masters recorded the highest number of champion points in three of the five decades evaluated, the 1960s, ’90s and 2000s. The British Open won the 1970s and ’80s. The Masters never finished below second in champion points in any of the five decades evaluated.

- The U.S. Open finished as high as second in just two decades, the 1960s and ’90s, and finished last in champion points in the 1970s and 2000s.

Best Decade for Major Winners, the 1970s

- Both the British Open and PGA Championship had their highest number of champion points in the 1970s, more than any of the five decades evaluated.

- This contributed to the 1970s being a golden era for major winners. With 392 points spread among 40 majors, the average major champion ranked in the No. 12 to 15 range out of all 120 major champions since 1960 (see Top 40 +Golfers chart). The next best decade was the 1960s with 367 champion points.

1990s Recorded Fewest Champion Points of Any Decade

- The average number of champion points recorded in each decade, other than the 1990s, was about 360 points (362.5). This average is 77 points higher than the total number of champion points recorded in the 1990s — just 285.

- The average winner of a major in the 1990s was a champion ranked in the No. 21 to 30 range of all 120 major winners since 1960 (see Top 40+ Golfers chart).

Can a Non-Major Winner Still be Ranked Among the Greats?

- This is a controversial topic, but some insight can be offered through the method proposed here. For example, if we were to look at the record of Colin Montgomerie, he would have 32 champion points based on 31 Euro Tour wins and nine “other wins” worth one point.

- This would place him solidly in champion tier No. 6 alongside such players as multiple major winners Fuzzy Zoeller, John Daly and Rory McIloroy (each with two majors) and other players such as Tom Kite and Davis Love (see Top 40+ Golfers chart).

- Since Monty did not win a major, however, he is not included in this evaluation.

So given the USGA’s/Sandy Tatum’s stated goal of “identifying the best golfers in the world,” how well has the U.S. Open done?

The U.S. Open has had its share of highly accomplished champions since 1960 with multiple winners that include Jack, Tiger, Irwin, Casper, Trevino and others. But by most reasonable measures, and the methodology presented here, it is clear our national open often crowns champions whose career records are well below the all-time greats. Here are the U.S. Open victors since 1960 who amassed the fewest champion points in this evaluation, starting with the most recent:

Of course, we can expect some of the active players listed will add to their career accomplishments, taking them to a higher champion tier, but at a minimum the data shows that the U.S. Open crowns a “surprise champion” at least once a decade, or 1 in 9 on average (six in the past 54 years). This could go to 15 percent, nearly 1 in 6, if two of the five active players below age 40 don’t move up significantly in time and another surprise champion is crowned the next few years.

This is actually a more favorable percentage for the U.S. Open than it had in the 1950s, which saw three surprise champions: Ed Furgol, 1954 (five other PGA Tour wins), Jack Fleck, 1955 (two other PGA Tour wins) and Dick Mayer, 1957 (six other PGA Tour wins). It’s hard to go back further than the 1950s because the national open wasn’t played during World War II (1942-45), and pro golf tours were still in the early stages, so there were far fewer opportunities for a player to build his career accomplishments.

The facts are that the U.S. Open has long produced surprising winners starting with Francis Ouimet’s victory in 1913 that shocked the sporting world. It has also produced disappointments, even heartbreaks, with all-time greats like Sam Snead failing to capture the title and Phil’s six runner-up finishes to date.

This month golf fans are already focusing their attention on Pinehurst and asking if Phil will finally break through, will some other big name add to his career achievements, or will our national open crown another surprise champion? Whatever the outcome, the U.S. Open will again have identified the “best player in the world.” Maybe not the best over a full career, but certainly the best of the week just as it has many times before.

- LIKE0

- LEGIT0

- WOW0

- LOL0

- IDHT0

- FLOP0

- OB0

- SHANK0

19th Hole

Vincenzi’s 2024 Zurich Classic of New Orleans betting preview

The PGA TOUR heads to New Orleans to play the 2023 Zurich Classic of New Orleans. In a welcome change from the usual stroke play, the Zurich Classic is a team event. On Thursday and Saturday, the teams play best ball, and on Friday and Sunday the teams play alternate shot.

TPC Louisiana is a par 72 that measures 7,425 yards. The course features some short par 4s and plenty of water and bunkers, which makes for a lot of exciting risk/reward scenarios for competitors. Pete Dye designed the course in 2004 specifically for the Zurich Classic, although the event didn’t make its debut until 2007 because of Hurricane Katrina.

Coming off of the Masters and a signature event in consecutive weeks, the field this week is a step down, and understandably so. Many of the world’s top players will be using this time to rest after a busy stretch.

However, there are some interesting teams this season with some stars making surprise appearances in the team event. Some notable teams include Patrick Cantlay and Xander Schauffele, Rory McIlroy and Shane Lowry, Collin Morikawa and Kurt Kitayama, Will Zalatoris and Sahith Theegala as well as a few Canadian teams, Nick Taylor and Adam Hadwin and Taylor Pendrith and Corey Conners.

Past Winners at TPC Louisiana

- 2023: Riley/Hardy (-30)

- 2022: Cantlay/Schauffele (-29)

- 2021: Leishman/Smith (-20)

- 2019: Palmer/Rahm (-26)

- 2018: Horschel/Piercy (-22)

- 2017: Blixt/Smith (-27)

2024 Zurich Classic of New Orleans Picks

Tom Hoge/Maverick McNealy +2500 (DraftKings)

Tom Hoge is coming off of a solid T18 finish at the RBC Heritage and finished T13 at last year’s Zurich Classic alongside Harris English.

This season, Hoge is having one of his best years on Tour in terms of Strokes Gained: Approach. In his last 24 rounds, the only player to top him on the category is Scottie Scheffler. Hoge has been solid on Pete Dye designs, ranking 28th in the field over his past 36 rounds.

McNealy is also having a solid season. He’s finished T6 at the Waste Management Phoenix Open and T9 at the PLAYERS Championship. He recently started working with world renowned swing coach, Butch Harmon, and its seemingly paid dividends in 2024.

Keith Mitchell/Joel Dahmen +4000 (DraftKings)

Keith Mitchell is having a fantastic season, finishing in the top-20 of five of his past seven starts on Tour. Most recently, Mitchell finished T14 at the Valero Texas Open and gained a whopping 6.0 strokes off the tee. He finished 6th at last year’s Zurich Classic.

Joel Dahmen is having a resurgent year and has been dialed in with his irons. He also has a T11 finish at the PLAYERS Championship at TPC Sawgrass which is another Pete Dye track. With Mitchell’s length and Dahmen’s ability to put it close with his short irons, the Mitchell/Dahmen combination will be dangerous this week.

Taylor Moore/Matt NeSmith +6500 (DraftKings)

Taylor Moore has quickly developed into one of the more consistent players on Tour. He’s finished in the top-20 in three of his past four starts, including a very impressive showing at The Masters, finishing T20. He’s also finished T4 at this event in consecutive seasons alongside Matt NeSmith.

NeSmith isn’t having a great 2024, but has seemed to elevate his game in this format. He finished T26 at Pete Dye’s TPC Sawgrass, which gives the 30-year-old something to build off of. NeSmith is also a great putter on Bermudagrass, which could help elevate Moore’s ball striking prowess.

- LIKE8

- LEGIT3

- WOW1

- LOL1

- IDHT0

- FLOP3

- OB1

- SHANK1

19th Hole

Vincenzi’s 2024 LIV Adelaide betting preview: Cam Smith ready for big week down under

After having four of the top twelve players on the leaderboard at The Masters, LIV Golf is set for their fifth event of the season: LIV Adelaide.

For both LIV fans and golf fans in Australia, LIV Adelaide is one of the most anticipated events of the year. With 35,000 people expected to attend each day of the tournament, the Grange Golf Club will be crawling with fans who are passionate about the sport of golf. The 12th hole, better known as “the watering hole”, is sure to have the rowdiest of the fans cheering after a long day of drinking some Leishman Lager.

The Grange Golf Club is a par-72 that measures 6,946 yards. The course features minimal resistance, as golfers went extremely low last season. In 2023, Talor Gooch shot consecutive rounds of 62 on Thursday and Friday, giving himself a gigantic cushion heading into championship Sunday. Things got tight for a while, but in the end, the Oklahoma State product was able to hold off The Crushers’ Anirban Lahiri for a three-shot victory.

The Four Aces won the team competition with the Range Goats finishing second.

*All Images Courtesy of LIV Golf*

Past Winners at LIV Adelaide

- 2023: Talor Gooch (-19)

Stat Leaders Through LIV Miami

Green in Regulation

- Richard Bland

- Jon Rahm

- Paul Casey

Fairways Hit

- Abraham Ancer

- Graeme McDowell

- Henrik Stenson

Driving Distance

- Bryson DeChambeau

- Joaquin Niemann

- Dean Burmester

Putting

- Cameron Smith

- Louis Oosthuizen

- Matt Jones

2024 LIV Adelaide Picks

Cameron Smith +1400 (DraftKings)

When I pulled up the odds for LIV Adelaide, I was more than a little surprised to see multiple golfers listed ahead of Cameron Smith on the betting board. A few starts ago, Cam finished runner-up at LIV Hong Kong, which is a golf course that absolutely suits his eye. Augusta National in another course that Smith could roll out of bed and finish in the top-ten at, and he did so two weeks ago at The Masters, finishing T6.

At Augusta, he gained strokes on the field on approach, off the tee (slightly), and of course, around the green and putting. Smith able to get in the mix at a major championship despite coming into the week feeling under the weather tells me that his game is once again rounding into form.

The Grange Golf Club is another course that undoubtedly suits the Australian. Smith is obviously incredibly comfortable playing in front of the Aussie faithful and has won three Australian PGA Championship’s. The course is very short and will allow Smith to play conservative off the tee, mitigating his most glaring weakness. With birdies available all over the golf course, there’s a chance the event turns into a putting contest, and there’s no one on the planet I’d rather have in one of those than Cam Smith.

Louis Oosthuizen +2200 (DraftKings)

Louis Oosthuizen has simply been one of the best players on LIV in the 2024 seas0n. The South African has finished in the top-10 on the LIV leaderboard in three of his five starts, with his best coming in Jeddah, where he finished T2. Perhaps more impressively, Oosthuizen finished T7 at LIV Miami, which took place at Doral’s “Blue Monster”, an absolutely massive golf course. Given that Louis is on the shorter side in terms of distance off the tee, his ability to play well in Miami shows how dialed he is with the irons this season.

In addition to the LIV finishes, Oosthuizen won back-to-back starts on the DP World Tour in December at the Alfred Dunhill Championship and the Mauritus Open. He also finished runner-up at the end of February in the International Series Oman. The 41-year-old has been one of the most consistent performers of 2024, regardless of tour.

For the season, Louis ranks 4th on LIV in birdies made, T9 in fairways hit and first in putting. He ranks 32nd in driving distance, but that won’t be an issue at this short course. Last season, he finished T11 at the event, but was in decent position going into the final round but fell back after shooting 70 while the rest of the field went low. This season, Oosthuizen comes into the event in peak form, and the course should be a perfect fit for his smooth swing and hot putter this week.

- LIKE12

- LEGIT3

- WOW1

- LOL1

- IDHT0

- FLOP1

- OB1

- SHANK1

Opinion & Analysis

The Wedge Guy: What really makes a wedge work? Part 1

Of all the clubs in our bags, wedges are almost always the simplest in construction and, therefore, the easiest to analyze what might make one work differently from another if you know what to look for.

Wedges are a lot less mysterious than drivers, of course, as the major brands are working with a lot of “pixie dust” inside these modern marvels. That’s carrying over more to irons now, with so many new models featuring internal multi-material technologies, and almost all of them having a “badge” or insert in the back to allow more complex graphics while hiding the actual distribution of mass.

But when it comes to wedges, most on the market today are still single pieces of molded steel, either cast or forged into that shape. So, if you look closely at where the mass is distributed, it’s pretty clear how that wedge is going to perform.

To start, because of their wider soles, the majority of the mass of almost any wedge is along the bottom third of the clubhead. So, the best wedge shots are always those hit between the 2nd and 5th grooves so that more mass is directly behind that impact. Elite tour professionals practice incessantly to learn to do that consistently, wearing out a spot about the size of a penny right there. If impact moves higher than that, the face is dramatically thinner, so smash factor is compromised significantly, which reduces the overall distance the ball will fly.

Every one of us, tour players included, knows that maddening shot that we feel a bit high on the face and it doesn’t go anywhere, it’s not your fault.

If your wedges show a wear pattern the size of a silver dollar, and centered above the 3rd or 4th groove, you are not getting anywhere near the same performance from shot to shot. Robot testing proves impact even two to three grooves higher in the face can cause distance loss of up to 35 to 55 feet with modern ‘tour design’ wedges.

In addition, as impact moves above the center of mass, the golf club principle of gear effect causes the ball to fly higher with less spin. Think of modern drivers for a minute. The “holy grail” of driving is high launch and low spin, and the driver engineers are pulling out all stops to get the mass as low in the clubhead as possible to optimize this combination.

Where is all the mass in your wedges? Low. So, disregarding the higher lofts, wedges “want” to launch the ball high with low spin – exactly the opposite of what good wedge play requires penetrating ball flight with high spin.

While almost all major brand wedges have begun putting a tiny bit more thickness in the top portion of the clubhead, conventional and modern ‘tour design’ wedges perform pretty much like they always have. Elite players learn to hit those crisp, spinny penetrating wedge shots by spending lots of practice time learning to consistently make contact low in the face.

So, what about grooves and face texture?

Grooves on any club can only do so much, and no one has any material advantage here. The USGA tightly defines what we manufacturers can do with grooves and face texture, and modern manufacturing techniques allow all of us to push those limits ever closer. And we all do. End of story.

Then there’s the topic of bounce and grinds, the most complex and confusing part of the wedge formula. Many top brands offer a complex array of sole configurations, all of them admittedly specialized to a particular kind of lie or turf conditions, and/or a particular divot pattern.

But if you don’t play the same turf all the time, and make the same size divot on every swing, how would you ever figure this out?

The only way is to take any wedge you are considering and play it a few rounds, hitting all the shots you face and observing the results. There’s simply no other way.

So, hopefully this will inspire a lively conversation in our comments section, and I’ll chime in to answer any questions you might have.

And next week, I’ll dive into the rest of the wedge formula. Yes, shafts, grips and specifications are essential, too.

- LIKE32

- LEGIT7

- WOW1

- LOL1

- IDHT2

- FLOP3

- OB1

- SHANK3

-

19th Hole2 weeks ago

19th Hole2 weeks agoDave Portnoy places monstrous outright bet for the 2024 Masters

-

19th Hole3 days ago

19th Hole3 days agoJustin Thomas on the equipment choice of Scottie Scheffler that he thinks is ‘weird’

-

19th Hole2 weeks ago

19th Hole2 weeks agoTiger Woods arrives at 2024 Masters equipped with a putter that may surprise you

-

19th Hole3 days ago

19th Hole3 days ago‘Absolutely crazy’ – Major champ lays into Patrick Cantlay over his decision on final hole of RBC Heritage

-

19th Hole3 weeks ago

19th Hole3 weeks agoReport: Tiger Woods has ‘eliminated sex’ in preparation for the 2024 Masters

-

19th Hole1 week ago

19th Hole1 week agoTwo star names reportedly blanked Jon Rahm all week at the Masters

-

19th Hole1 week ago

19th Hole1 week agoReport: LIV Golf identifies latest star name they hope to sign to breakaway tour

-

19th Hole1 week ago

19th Hole1 week agoNeal Shipley presser ends in awkward fashion after reporter claims Tiger handed him note on 8th fairway

Sean

Jun 14, 2014 at 7:28 am

I think the Masters is the “easiest” major to win since it has the smallest field, i.e., amateurs, past champions well past their prime, etc. So the odds of winning it increase, as opposed to the other majors. In addition, the course isn’t as difficult as, for example, the US Open. In my opinion the US Open identifies the best player simply because the set-up of the tournament is the most difficult year in and year out. The Open Championship can be, but is weather dependent.

ben

Jun 10, 2014 at 4:28 am

I think this is an excellent report. Well researched and with plenty of valid and interesting data. And what I glean from it all is that The Open Championship (British open) is the premier event for identifying the best player. It may be a close second to the Masters but the Masters has pretty much a full field of, well, ‘masters’ hence why it usually produces a ‘master’ as a champion. The fact that The British Open ranks so highy on the list despite being the world’s Open and having a huge portion of it’s field come from qualifiers around the world I think that proves it is the best Championship for producing the best champion. . This then raises another interesting point: are links courses the best courses for finding out the best golfer? I’d suggest they are and they do. .

Gerald Nagler

Jun 11, 2014 at 6:00 pm

Thanks for everyone’s comments. I think Ben really has this right. After evaluating the last 50+ years of majors, The Masters comes out on top in terms of crowning golf’ greatest champions but only by a slight margin. The British Open is close behind with full fields, changing venues, bad weather, quirky bounces, etc. In fact during the 1970s, the only golfer to win the Open Championship not in the Hall of Fame is Tom Weiskopf, and he’s hardly chopped liver. The Masters, as some point out, benefits from its smaller fields, same course, favorable springtime conditions and the like, but all these taken together only give it a slight edge over the British Open. As for the US Open, I would like to hear why readers think it crowns so many surprise champions. One “what if” scenario worth noting about the US Open – it would have finished even lower in the evaluation IF Hale Irwin in the 1990 US Open at Medinah hadn’t holed a 45 foot birdie putt on the 72nd hole to get into a playoff with Mike Donald that Irwin won the next day on the 19th hole. If Donald had won, and he came mighty close more than once to pulling it off, the US Open would have nearly the same number of champion points as the PGA Championship (assuming Donald, following his US Open victory, didn’t dramatically add to his record of one other PGA Tour win the year before). I expect there many are other “what ifs” we can play with each major but the question stands, why doesn’t the cream rise to the top in the US Open as it does with the British Open?

Steve

Jun 9, 2014 at 9:59 am

Dumb. First of all the Masters as an invitational has a clear advantage. It is also on the same course each year so it would appear that the best have a greater chance to figure it out and win. The US Open is just that, an Open championship that creates a higher diversity of player and course opportunity each year. Frankly those who win multiple opens on different courses have my greater respect. Otherwise who cares. They are all tests and fun to watch.

Rich

Jun 9, 2014 at 2:03 am

It would appear that the more words you write and the more data you give, increases your chances of being published on Golfwrx, no matter how bad your article is. What a load of rubbish. Let’s just watch the majors and enjoy them. Bring on the US open! Good luck all you qualifiers!

Dan

Jun 9, 2014 at 12:53 am

It would be interesting to see how me champions points the players gets. See how it would rank as the 5th major. Would it be in 5th place or higher up?

Jm

Jun 8, 2014 at 8:43 pm

I think the more relevant question is which tournament, major or not, does the best job of identifying the best player that week. And even that question is fraught with endless analysis.

cash banister

Jun 8, 2014 at 8:08 pm

“Which major crowns golf’s greatest champions?”

—————————————————

That is one of the most poorly constructed sentences that I have ever seen. A better question is “WTF ever happened to professionalism in journalism?”

Jim Zimmerman

Jun 8, 2014 at 7:44 pm

This methodology is absurd and the Masters entrance criteria is a tautology that gives the event a fake air of identifying the best champions. The Masters field has many past champions and amateurs who pose no threat to the limited field of elites. Even if a past champion has a crazy lucky week as a past champion it just adds to his “luster” as a major champion and doesn’t affect the status other than to actually increase it. On the other hand OPEN events that allow ALL of the players in who could reasonably contend are by far the best way to identify the best players. Look at how two time major champion Daly was seldom able to even compete at Augusta, never mind that it was being played on a long and open course that suited his game to a tee. The Masters by its entrance criteria seeks to guarantee that a long shot can never win since for the most part he won’t even get to tee it up.

Jm

Jun 8, 2014 at 8:37 pm

Exactly. The masters will never have too many “scrubs” as champions because they simply are not invited to play.

And that is exactly one of the many reasons i love the Masters.

The US Open is designed to identify the best player for that particular week which it usually does based on the USGA definition of what a good player plays like.

This article has a good premise but poor execution and insufficient analysis.

It is way more complicated to figure out than what is laid out in this article in my opinion

Jim Zimmerman

Jun 9, 2014 at 11:07 am

@Jm what do you have against good golfers who qualify for open championships but aren’t invited to tournaments like the Masters. To tweak John Daly a little bit yesterday I watched an 11 hole sudden death playoff for the Cleveland Open on the web.com tour where the guy who won it had played 36 holes that week to qualify for next week’s US Open. THAT is the type of player I want to see in the Masters! As someone else mentioned another factor is the Masters LOCAL knowledge affect the course is so different on the green complexes that once again the already qualified STAR has a huge advantage. Look at how Lee Trevino analyzes the game and HATED the Masters, starting out he was BETTER than Ray Floyd but NOT in the Masters, it took a US Open or two for Lee’s game to be ALLOWED to shine, shame on the Masters and its idiotic entrance criteria!

Rich

Jun 9, 2014 at 6:03 pm

It might be going a bit far to call it idiotic. It’s just different.