Instruction

Teaching feel in putting

One of the most enigmatic portions of putting has been the relationship between line and speed. Golfers know that their lines are determined by the speed in which they hit a putt, but how do they know how hard to hit it?

What I’m after is the answer to the age-old question, “How do you teach feel?” Isn’t there a more scientific way than what instructors have taught in the past to audit feel and help people to become better at consistently hitting their putts the same distance?

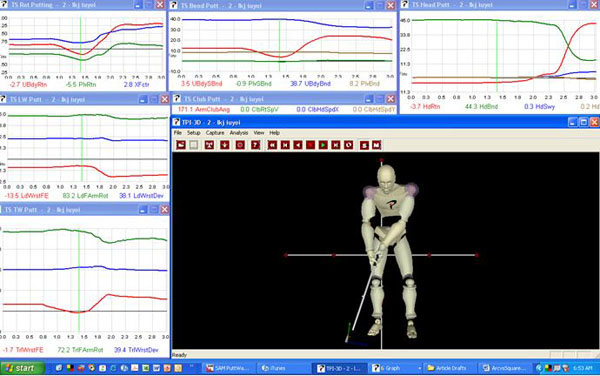

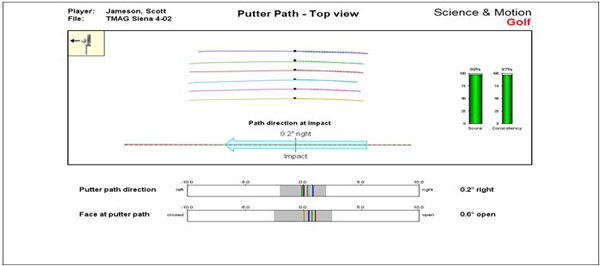

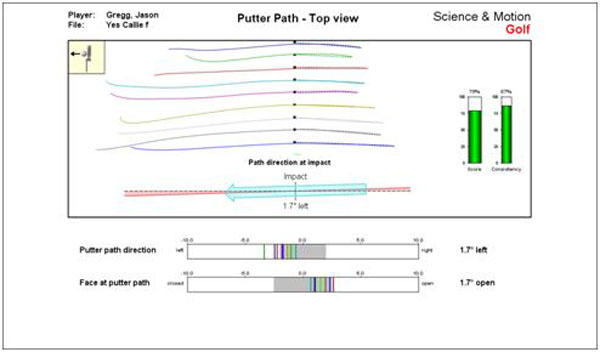

In my putting academy, I use Advanced Motion Measurement’s 3D Motion Analysis System and the SAM Puttlab by Science & Motion Sports to teach “feel.” These two high-tech systems will be used to correlate the data contained below.

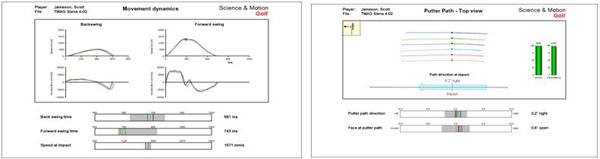

The SAM Analysis above shows the “time signatures” and “stroke lengths” of 10 putts in succession charting the backswing speed, forward swing speed, time to impact and overall putter head acceleration during the differing strokes. These “signatures” as compared to the overall “length” of the putting stroke help us see the consistency of one’s stroke dynamics and discover whether or not “feel” can be taught or not.

- The top-left time graph (in image 2 below) pertains to putter head speed on the way back. It shows just how fast the putter is moving in milliseconds. The Tour average is around 650 ms.

- The top-right time graph shows the speed of the putter into the forward swing, through impact and into the finish. The Tour average is around 300 ms.

- The bottom-left time graph is the acceleration of the putter from address to the top of the backstroke. A flat line shows that acceleration is constant, thus the speed of the putter head at this point is neither accelerating nor decelerating.

- The bottom-right time graph shows the transitional acceleration of the putter into the forward swing and on to the finish. The steeper the line moves up, the more putter acceleration there is and the faster the putter is moving in milliseconds. If the line descends, then the putter acceleration is slowing and its speed is diminishing.

Image 2

The movement dynamics of the above player’s motion shows a wonderful timing signature as all of the lines on the four graphs are not jagged during the backswing and/or forward swing. This shows consistency within this player’s putter head speed and putter head acceleration back and through.

In viewing the putter path length graph, this professional player was asked to hit the same 15-foot putt over and over while this data was taken. Subsequently, the backswing length and forward swing length are symmetrical indicating consistency within the length of stroke. When you take a couple controlled length strokes with the same type of “timing signature” for each putt, you will find the ball wanting to move the same distance unless an outside force acts upon it, changing its roll. Think of wind, dead spots on the green, etc.

One note regarding your “stroke length” and “timing signatures:” It is very easy to repeat a stroke that is consistent in length, acceleration and timing if and only if your impact alignments are sound and solid. We never want a golfer’s wrists to take over and power the stroke. In a perfect world, we only want them to react to the motions of your shoulders and arms.

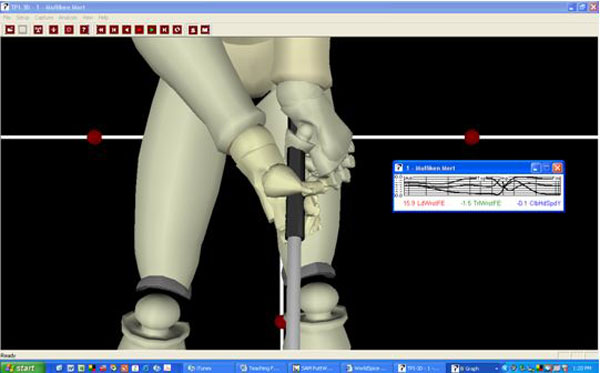

The 3D analysis of the professional used in the “correct” putting sample graphs above shows that at impact the forward wrist and rear wrists are in solid alignments as the shaft is leaning 0.1 degrees forward. This is the most consistent impact position that you can have. Whenever the forward wrist “breaks down” and the club shaft leans back through impact, a golfer has added loft to the putter face. That makes “feel” almost impossible to have when a golfer needs it.

As you compare the speed and acceleration graphs between the professional player in image 2 and the mid-handicap amateur below in image 5, you will notice a huge difference between the consistency of the “signatures,” as well as poor control of the putting stroke length back and through.

Image 5

Examining the four graphs in image 5 helps us to see that each of these strokes had a very different “timing signature” and logically, if you cannot move the putter back and through the same speed on the same length putt you are going to have problems with pace.

Not only does this player have trouble controlling the speed and acceleration of his putter, but he also has issues controlling the length of his stroke back and through. Remember that this mid-handicap player was asked to hit the SAME length putt over and over (15 feet) and this lack of consistently shows that his player cannot control his speed/acceleration or his backstroke/follow-through swing length. This makes it very hard for this player to develop a consistent “feel” on the greens because nothing is constant from putt to putt and stroke to stroke.

Now the point must be made: Did this player have trouble with his speed because his swing length was off or was he having trouble with his swing length because his speed was off? I believe that it can happen either way! Someone who takes the putter back “super slow” will often adjust and move through impact much faster, however, the opposite argument can be made that when this player takes the club back too long or too short. His subconscious takes over and adjusts his swing forward swing length to accommodate. When this reaction occurs, a golfer’s timing signatures will become grossly inconsistent.

The Mechanical Conclusion: My 3D analysis and the SAM data prove that in order to have “feel” on the greens, golfers must do several things in order to reproduce the same stroke:

- They must control the overall length of their backstroke and follow-through on putts with the same general length.

- They must control not only the overall speed of their overall stroke, but its acceleration as well; thus, all the lines on each graphs will almost appear as “one.”

- For “swing” putters like Ben Crenshaw, they must accelerate into the impact zone, maintaining a constant velocity through impact in order to control the ball’s reaction. This is shown on the bottom right graph by the “table-top” looking acceleration curve. Impact occurs at the point where the “table-top” falls off on the right side. This is the acceleration signature of a player who plays on fast greens.

- As a “hit” putter like Nick Price, golfers must accelerate in the beginning of the backstroke and into to the ball with a “popping” type of action. This is shown on the bottom right graph as acceleration begins. It table-tops just before impact and then accelerates once again into the ball (shown by the steep peak) and then drops off rapidly. The second acceleration is the “pop” through impact seen by Price and is usually a mark of someone who has grown up on slower greens.

- During the forward swing and into and through impact, a golfer’s wrists should remain as solid as possible allowing the club shaft to return to the golf ball in a position that will allow it to propel the ball as consistently as possible.

Can we teach really teach any type of “feel” to the sample player who had poor length control and poor timing to his speed and acceleration signatures? The answer is YES, and here is how I did it for one of my students.

The “Feel” Procedure

First, instructors must help this player to understand why he has no feel and why he cannot control his pace on the greens. This was accomplished by showing him his stroke length graph as well as his stroke timing graphs. He was told to keep the thoughts simple and just to understand that his backstroke length varied widely and he could not control the timing of his stroke. Whether this was mainly due to his backstroke length or his backstroke speed was not of interest.

Second, in a logical format, he was given biofeedback with the SAM unit so that he could actually monitor the length of his backswing on the sample 15-foot putt.

Third, once he began to show some type of a consistent feel to the length of this putt, it was time to introduce another thought.

Fourth, he was told to make the same length of stroke but to find a “natural” tempo for his backstroke to follow. My thinking was that if we could get him to make consistent length strokes at the same pace, the forward swing would take care of itself.

Fifth, after many rounds of testing this proved to be the key to him “improving or learning” feel. What was discovered was that if the stroke was allowed to lengthen then this player’s putter pace tried to make up for the faulty backswing through the ball causing poor timing signatures.

Note: In further testing, some players had the opposite problem and had to control the speed of the backstroke for the putter length to become consistent. These people were the exception, however, and not the norm. It seemed that it was much easier for players to control their length first and then control the speed of this new stroke on the way back. After one week of SAM training with the biofeedback, it was decided that this was the proper training protocol for this player.

In conclusion, if you have trouble with your feel, you must monitor your stroke length and pace while maintaining proper impact alignments. When most people “lose their feel” the length of the stroke becomes inconsistent for the putt at hand and the backstroke speed and acceleration suffer as a result. The only thing for your body to do is to try and amend the flaw on the way through by changing their forward swing length, speed and acceleration.

- LIKE0

- LEGIT0

- WOW0

- LOL1

- IDHT0

- FLOP0

- OB0

- SHANK0

Instruction

The Wedge Guy: The easiest-to-learn golf basic

My golf learning began with this simple fact – if you don’t have a fundamentally sound hold on the golf club, it is practically impossible for your body to execute a fundamentally sound golf swing. I’m still a big believer that the golf swing is much easier to execute if you begin with the proper hold on the club.

As you might imagine, I come into contact with hundreds of golfers of all skill levels. And it is very rare to see a good player with a bad hold on the golf club. There are some exceptions, for sure, but they are very few and very far between, and they typically have beat so many balls with their poor grip that they’ve found a way to work around it.

The reality of biophysics is that the body moves only in certain ways – and the particulars of the way you hold the golf club can totally prevent a sound swing motion that allows the club to release properly through the impact zone. The wonderful thing is that anyone can learn how to put a fundamentally sound hold on the golf club, and you can practice it anywhere your hands are not otherwise engaged, like watching TV or just sitting and relaxing.

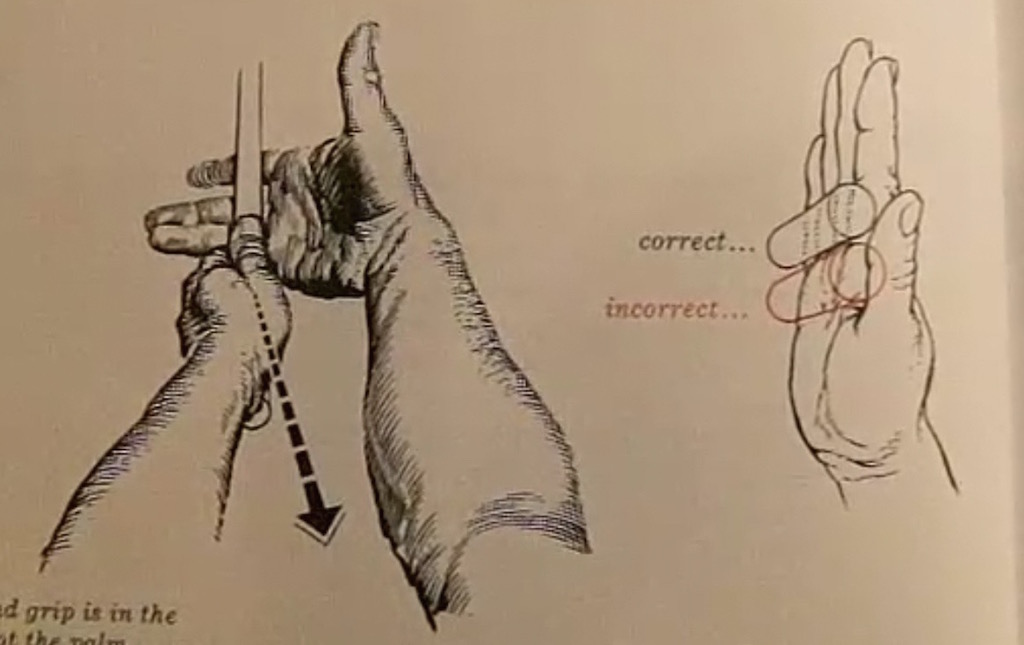

Whether you prefer an overlap, interlock or full-finger (not baseball!) grip on the club, the same fundamentals apply. Here are the major grip faults I see most often, in the order of the frequency:

Mis-aligned hands

By this I mean that the palms of the two hands are not parallel to each other. Too many golfers have a weak left hand and strong right, or vice versa. The easiest way to learn how to hold the club with your palms aligned properly is to grip a plain wooden ruler or yardstick. It forces the hands to align properly and shows you how that feels. If you grip and re-grip a yardstick several times, then grip a club, you’ll see that the learning curve is almost immediate.

The position of the grip in the upper/left hand

I also observe many golfers who have the butt of the grip too far into the heel pad of the upper hand (the left hand for right-handed players). It’s amazing how much easier it is to release the club through the ball if even 1/4-1/2″ of the butt is beyond the left heel pad. Try this yourself to see what I mean. Swing the club freely with just your left hand and notice the difference in its release from when you hold it at the end of the grip, versus gripping down even a half inch.

To help you really understand how this works, go to the range and hit shots with your five-iron gripped down a full inch to make the club the same length as your seven-iron. You will probably see an amazing shot shape difference, and likely not see as much distance loss as you would expect.

Too much lower (right) hand on the club

It seems like almost all golfers of 8-10 handicap or higher have the club too far into the palm of the lower hand, because that feels “good” if you are trying to control the path of the clubhead to the ball. But the golf swing is not an effort to hit at the ball – it is a swing of the club. The proper hold on the club has the grip underneath the pad at the base of the fingers. This will likely feel “weak” to you — like you cannot control the club like that. EXACTLY. You should not be trying to control the club with your lower/master hand.

Gripping too tightly

Nearly all golfers hold the club too tightly, which tenses up the forearms and prevents a proper release of the club through impact. In order for the club to move back and through properly, you must feel that the club is controlled by the last three fingers of the upper hand, and the middle two fingers of the lower hand. If you engage your thumbs and forefingers in “holding” the club, the result will almost always be a grip that is too tight. Try this for yourself. Hold the club in your upper hand only, and squeeze firmly with just the last three fingers, with the forefinger and thumb off the club entirely. You have good control, but your forearms are not tense. Then begin to squeeze down with your thumb and forefinger and observe the tensing of the entire forearm. This is the way we are made, so the key to preventing tenseness in the arms is to hold the club very lightly with the “pinchers” — the thumbs and forefingers.

So, those are what I believe are the four fundamentals of a good grip. Anyone can learn them in their home or office very quickly. There is no easier way to improve your ball striking consistency and add distance than giving more attention to the way you hold the golf club.

More from the Wedge Guy

- The Wedge Guy: Golf mastery begins with your wedge game

- The Wedge Guy: Why golf is 20 times harder than brain surgery

- The Wedge Guy: Musings on the golf ball rollback

- LIKE86

- LEGIT13

- WOW6

- LOL1

- IDHT0

- FLOP4

- OB1

- SHANK8

Instruction

Clement: Stop ripping off your swing with this drill!

Not the dreaded headcover under the armpit drill! As if your body is defective and can’t function by itself! Have you seen how incredible the human machine is with all the incredible feats of agility all kinds of athletes are accomplishing? You think your body is so defective (the good Lord is laughing his head off at you) that it needs a headcover tucked under the armpit so you can swing like T-Rex?

- LIKE0

- LEGIT2

- WOW2

- LOL0

- IDHT0

- FLOP0

- OB0

- SHANK2

Instruction

How a towel can fix your golf swing

This is a classic drill that has been used for decades. However, the world of marketed training aids has grown so much during that time that this simple practice has been virtually forgotten. Because why teach people how to play golf using everyday items when you can create and sell a product that reinforces the same thing? Nevertheless, I am here to give you helpful advice without running to the nearest Edwin Watts or adding something to your Amazon cart.

For the “scoring clubs,” having a solid connection between the arms and body during the swing, especially through impact, is paramount to creating long-lasting consistency. And keeping that connection throughout the swing helps rotate the shoulders more to generate more power to help you hit it farther. So, how does this drill work, and what will your game benefit from it? Well, let’s get into it.

Setup

You can use this for basic chip shots up to complete swings. I use this with every club in my bag, up to a 9 or 8-iron. It’s natural to create incrementally more separation between the arms and body as you progress up the set. So doing this with a high iron or a wood is not recommended.

While you set up to hit a ball, simply tuck the towel underneath both armpits. The length of the towel will determine how tight it will be across your chest but don’t make it so loose that it gets in the way of your vision. After both sides are tucked, make some focused swings, keeping both arms firmly connected to the body during the backswing and follow through. (Note: It’s normal to lose connection on your lead arm during your finishing pose.) When you’re ready, put a ball in the way of those swings and get to work.

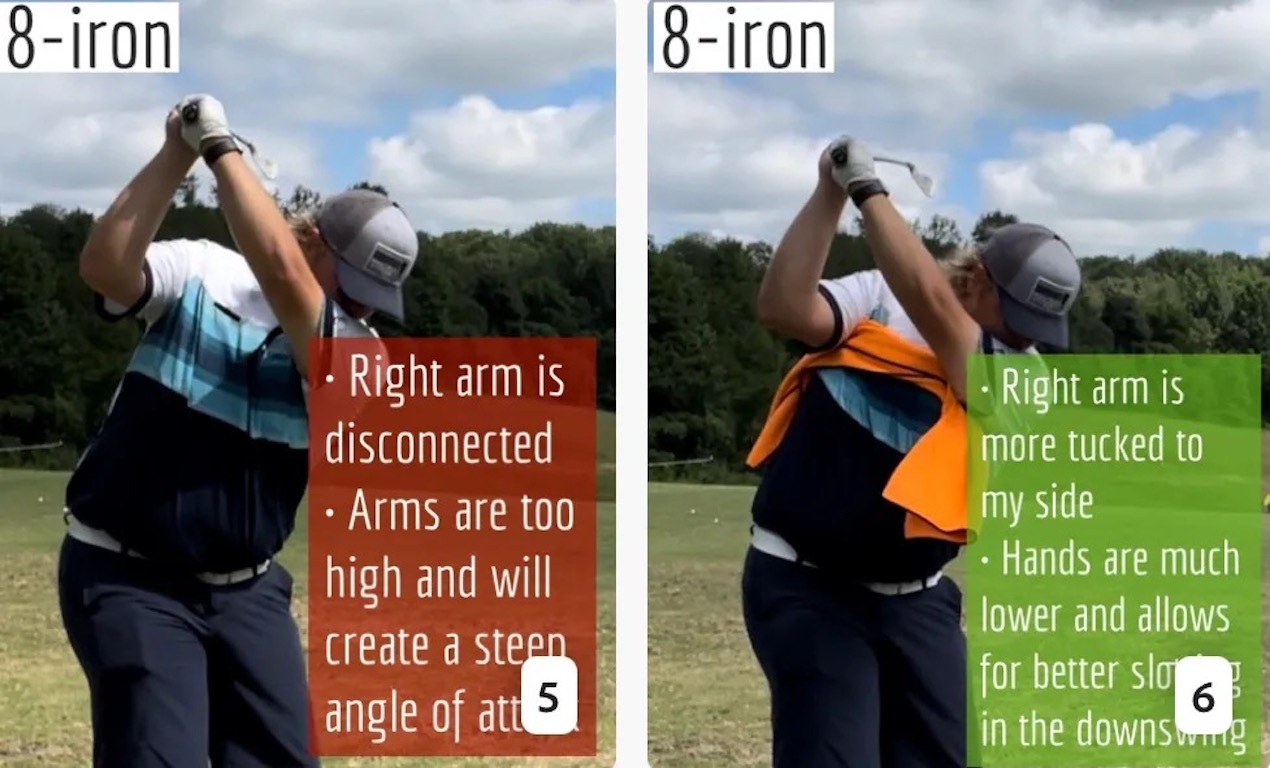

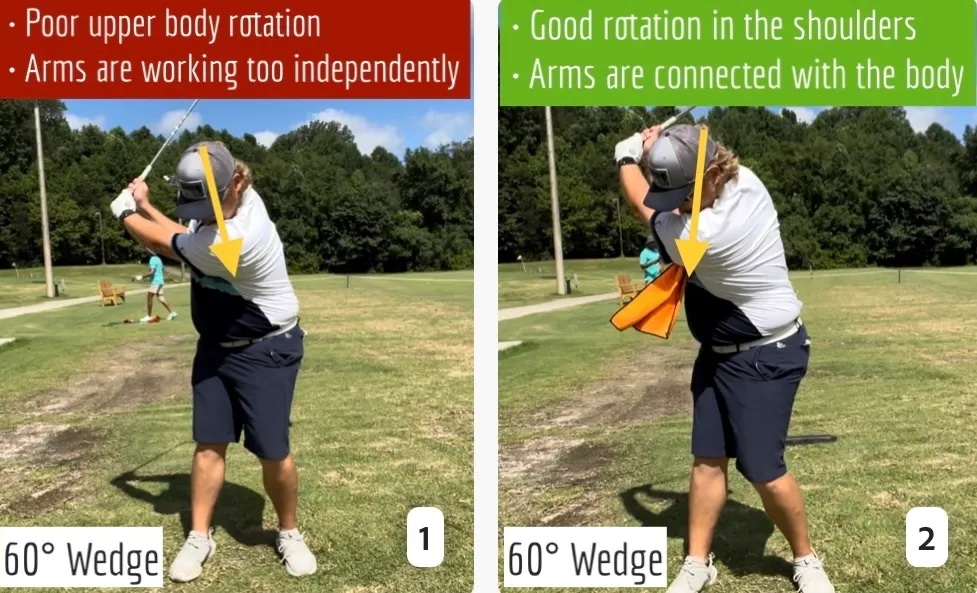

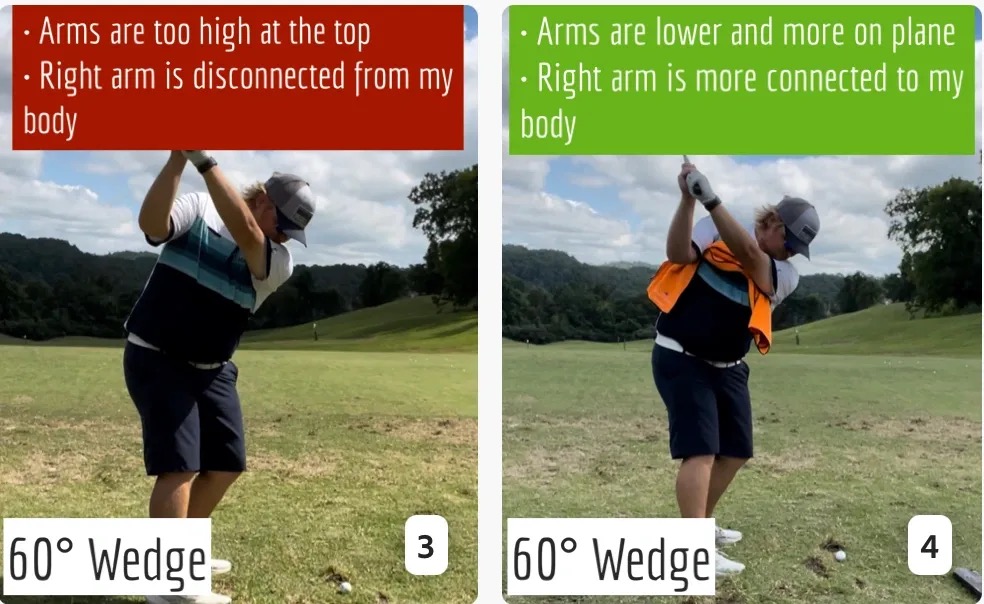

Get a Better Shoulder Turn

Many of us struggle to have proper shoulder rotation in our golf swing, especially during long layoffs. Making a swing that is all arms and no shoulders is a surefire way to have less control with wedges and less distance with full swings. Notice how I can get in a similar-looking position in both 60° wedge photos. However, one is weak and uncontrollable, while the other is strong and connected. One allows me to use my larger muscles to create my swing, and one doesn’t. The follow-through is another critical point where having a good connection, as well as solid shoulder rotation, is a must. This drill is great for those who tend to have a “chicken wing” form in their lead arm, which happens when it becomes separated from the body through impact.

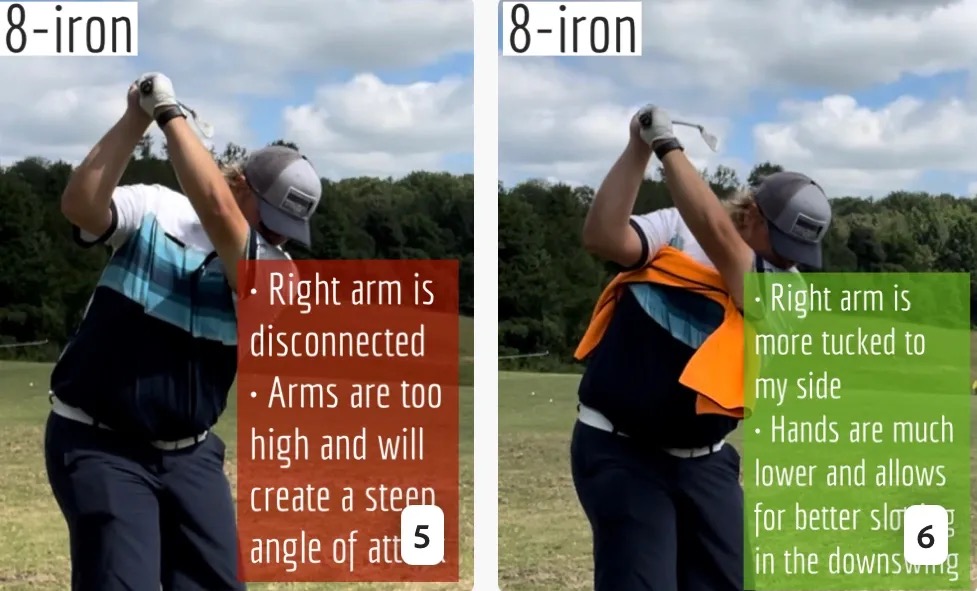

In full swings, getting your shoulders to rotate in your golf swing is a great way to reinforce proper weight distribution. If your swing is all arms, it’s much harder to get your weight to naturally shift to the inside part of your trail foot in the backswing. Sure, you could make the mistake of “sliding” to get weight on your back foot, but that doesn’t fix the issue. You must turn into your trial leg to generate power. Additionally, look at the difference in separation between my hands and my head in the 8-iron examples. The green picture has more separation and has my hands lower. This will help me lessen my angle of attack and make it easier to hit the inside part of the golf ball, rather than the over-the-top move that the other picture produces.

Stay Better Connected in the Backswing

When you don’t keep everything in your upper body working as one, getting to a good spot at the top of your swing is very hard to do. It would take impeccable timing along with great hand-eye coordination to hit quality shots with any sort of regularity if the arms are working separately from the body.

Notice in the red pictures of both my 60-degree wedge and 8-iron how high my hands are and the fact you can clearly see my shoulder through the gap in my arms. That has happened because the right arm, just above my elbow, has become totally disconnected from my body. That separation causes me to lift my hands as well as lose some of the extension in my left arm. This has been corrected in the green pictures by using this drill to reinforce that connection. It will also make you focus on keeping the lead arm close to your body as well. Because the moment either one loses that relationship, the towel falls.

Conclusion

I have been diligent this year in finding a few drills that target some of the issues that plague my golf game; either by simply forgetting fundamental things or by coming to terms with the faults that have bitten me my whole career. I have found that having a few drills to fall back on to reinforce certain feelings helps me find my game a little easier, and the “towel drill” is most definitely one of them.

- LIKE12

- LEGIT2

- WOW2

- LOL0

- IDHT0

- FLOP2

- OB0

- SHANK8

-

19th Hole2 weeks ago

19th Hole2 weeks agoDave Portnoy places monstrous outright bet for the 2024 Masters

-

19th Hole3 weeks ago

19th Hole3 weeks agoThings got heated at the Houston Open between Tony Finau and Alejandro Tosti. Here’s why

-

19th Hole2 weeks ago

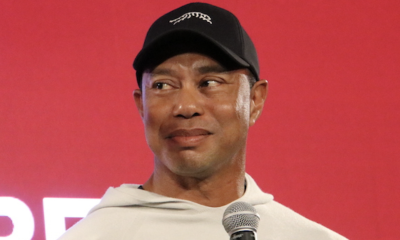

19th Hole2 weeks agoTiger Woods arrives at 2024 Masters equipped with a putter that may surprise you

-

19th Hole2 weeks ago

19th Hole2 weeks agoReport: Tiger Woods has ‘eliminated sex’ in preparation for the 2024 Masters

-

19th Hole6 days ago

19th Hole6 days agoTwo star names reportedly blanked Jon Rahm all week at the Masters

-

19th Hole6 days ago

19th Hole6 days agoNeal Shipley presser ends in awkward fashion after reporter claims Tiger handed him note on 8th fairway

-

19th Hole5 days ago

19th Hole5 days agoReport: LIV Golf identifies latest star name they hope to sign to breakaway tour

-

19th Hole3 weeks ago

19th Hole3 weeks agoAddiction, spinal fusion, and scam artists – Everything Anthony Kim revealed in candid interview with David Feherty

Selim

Feb 25, 2014 at 2:22 pm

Frankly, I could not read on after the first explanation of 4 graphs. Maybe it is because I am an engineer bit blatant disregard (or misrepresentation) of physics is annoying to say the least.

First graph: “tour speed is 650 ms”, is like saying a car travels 650 per hour. What is the distance that it travels in 650 milliseconds? That would be its speed (Speed = distance/time)

Second Graph: Same mistake, you are giving a measurement of time, not speed when you say 300ms.

Third graph: you say acceleration is constant meaning no acceleration or deceleration. Actually, the speed is constant only if acceleration is zero. In other times it means the speed is increasing or decreasing.

Maybe you think I am nitpicking but I can’t read a technical analysis if it is technically wrong.

Mark

Mar 1, 2014 at 3:53 pm

I agree. As an ME, I can’t help but notice the poor display of technical communication. I’m not saying that this whole article is wrong, but it definitely discredits the point when your analysis is not done correctly.

jeff

Feb 24, 2014 at 8:58 pm

Excellent

paul

Feb 24, 2014 at 8:37 pm

I love these very technical articles. I learned distance control with a putter on a simulator… If that’s not weird I don’t know what is. I spent an hour one day hitting putts to a virtual hole 15 feet away. And remembered the feel. Then did 45 foot putts for a while. If I know approximately how far away the hole is I just try and feel that distance in my head. Then putt. Seems to work. Played 18 holes by Vancouver a few weeks ago and distance control was never so good. (for uphill and downhill, think about feeling a few feet more or less)

Tom Stickney

Feb 25, 2014 at 9:27 am

Appreciate the comments. 🙂